Biblical Christianity in Four Parts – Part II

Testing popular Christian assumptions by holding them up to Biblical scrutiny.

Disembodiment: The Great Lie

For listeners: Listen on Spotify.

Note: if you haven't yet, check out Part One of this series here.

Contents

Intro

“If you died today, where would you go?”

If you have ever lasted until the end of a typical church service, I assume you have heard one of the elders ask this question, usually as one of the worship leaders plays the piano or guitar softly in the background. Before I expound on the question, I want to point out that this is not a bad way to end a Sunday morning service, at least in terms of cadence and structure.

Quite the contrary, it is an ideal denouement, a chance for those visiting and even the regular members to reflect on their standing with the God whose only passphrase for granting them salvation is that they merely believe.

And the journey we start after believing, with its sudden turns and pitfalls, convinces me it is never wrong for us to pause and reflect on our standing with God. However, if such reflection leads us anywhere, it should lead us to inspect the question of “where we go when we die” within a biblical framework. As we reflect, we might discover a set of untested assumptions beneath the question’s surface and at least two resulting fundamental errors.

The Assumptions

As to the set of assumptions, recall from Part One, where I quoted Sam Harris:

“The whole point of Christianity, or so it is imagined, is to safeguard the eternal wellbeing of human souls.”

(00:59:01)

As I expounded in that article, even if Sam Harris does not believe this to be the biblical point of Christianity, most Christians do and have elevated it to the status of ultimate good, hence the question, “If you died today…”.

The underlying assumptions upholding this belief are as follows:

This life, as we know i,t is our only opportunity to know Jesus and thus receive his salvation.

Humans are spiritual beings living in and constrained by material aspects.

As spiritual beings, humans possess innate immortality that allows the spirit or soul to transcend bodily existence when the body dies.

While I could rustle up a few more assumptions to add to the list above, I think these three are the most prominent within Christendom and impactful to our Christology. Besides, three is a complete number, and we only have so much time.

(Note: my goal is not to disprove these assumptions but to put them under biblical scrutiny.)

Assumption 1: This life as we know it is our only opportunity to know Jesus and thus receive his salvation.

Here is one of those firmly held beliefs we adopt at the start of our Christian journey, and I do not claim it is wrong.

It is the crux of the question, i.e., if you die today, you will either go to Heaven or Hell because it is only while you are alive that you can come to know Jesus and thus be saved. Indeed, to give the belief its due credit, this is a logical inference when we note the urgency that characterizes the New Testament, especially scriptures like Revelation 21:7-8.

But as I stated in my prologue:

…we find a culture uninterested in the Resurrection and with no urgency for repenting from dead works.

It is not that the New Testament does not impel us with its urgency. Rather, the New Testament’s urgency ought to impel us in a particular direction; it ought to drive us toward the Holy Spirit’s resurrection power to transform us from the inside out, taking all our fragments in Adam and reassembling them in Jesus. For what purpose? So that we may reflect Christ to the world and thus embody God’s promises to Israel through and through—Christ in us, the hope of glory.

Great, you might say. But this still demands that we know and confess Jesus as Lord, right? Yes, but also consider the following by C.S. Lewis:

“We do know that no man can be saved except through Christ; we do not know that only those who know him can be saved through him” (60).

I’ll allow you a moment to untangle that before moving on. But after untangling it, if you happen to disagree with Lewis (and my appeal to his authority), perhaps you will agree with scripture instead:

“Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?’

“The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’ (Matt. 25:37-40, NIV).

In case you missed it—the righteous have no idea that they have kept Christ’s commands and, likewise, that they ought to be saved. Furthermore, they are claiming to Jesus’ face that they have no memory of ever feeding him, giving him a drink, inviting him inside to warm up, or offering him an extra pair of pants. Although it seems they know enough to call him Lord, it is not self-evident from the text that they know who Jesus is or ought to know.

As to the specific notion that salvation is only available to us in this life as we know it (which I have not adequately addressed), let’s see how that idea fits into a well-known dark night of the soul: miscarriages, abortions, and the death of infants. All three are tragic. But under the shadow of Augustine’s doctrine of original sin, all three must warrant a one-way ticket to Hell—unless Christ’s saving power extends to those who do not consciously know or acknowledge him in this life as we know it.

Yet, because most of us cannot stomach the idea of babies going to an eternal Hell—with good reason—and because we cannot fit the “unless” contingency into our existing framework, we are compelled to drum up extra-biblical explanations to handle this “unique” case instead of what we ought to do, which is to return to our fundamental assumption and hold it under a biblical microscope.

Take the following by Gabriel Finocchio, a teacher I respect but must also disagree with on this point: “The second layer [of Hell] is the limbo of infants where those who die in original sin without any actual sin are confined and undergo some sort of holding” (00:10:59).

I want to say: are you joking? We cannot have it both ways—we cannot say in one breath that adults who never professed Jesus as their savior go to an eternal Hell, and in the next breath, say that babies are absolved because of the fine print about original versus actual sin.

(Regarding fine print, let me know where I can find this chapter and verse.)

To his credit, Finocchio admits that this is a speculative doctrine. Nevertheless, he resorts to it as the most definitive answer available rather than confront the underlying assumption forcing him into a philosophical corner—as do most Christians.

But suppose we draw a line from Romans 10:9 to Philippians 2:9-11. In that case, we get something like this:

“If you declare with your mouth, “Jesus is Lord,” and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.”

“Therefore God exalted him to the highest place / and gave him the name that is above every name, / that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, / in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord, / to the glory of God the Father.”

First, Romans provides us with the if/then conditional format for salvation, and then Philippians says, “Oh, by the way, everyone in heaven, on earth, and under the earth is going to meet this condition, so….”

Finally, consider Luke 20:38, where Jesus says of God, “‘He is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for to him all are alive.’”

To God, all are alive? It would seem so, according to the gospel. While I cannot speak with any authority about what we will face on judgment day, one thing remains biblically clear—we will all be alive: not in a holding place, not in a limbo of fathers or infants, but alive. Knowing what Jesus achieved through his bodily death and resurrection, how could it be otherwise? So, with that in mind, if I may be allowed to show the extent of my Latin, I conclude with this: “Dum spiro, spero.”

And then I defer to C.S. Lewis: we know some things but do not know others.

Assumption 2: Humans are spiritual beings living in and constrained by material aspects.

Of the three assumptions, this is perhaps the most harmful to the biblical framework because it stems from Platonic philosophy and early Gnostic teachings and so downgrades death from an enemy to a nuisance.

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, here is a good summary of Plato’s influence on Christian thought:

“We are urged to transform our values by taking to heart the greater reality of the forms and the defectiveness of the corporeal world. We must recognize that the soul is a different sort of object from the body—so much so that it does not depend on the existence of the body for its functioning, and can in fact grasp the nature of the forms far more easily when it is not encumbered by its attachment to anything corporeal” (Kraut, par. 2).

While the above summary is only a snapshot of Plato’s contribution to philosophy, I find it an alarmingly accurate description of what most Christians believe about the soul (or, in charismatic circles, the spirit). And like any skewed doctrine, it starts true, as we are “urged” to thoughtfully consider the “defectiveness” of our world. That is a biblical perspective, to be sure.

But biblically speaking, it falls apart when it dismisses the body as something that we are ultimately better off without, an idea that later formed the core of Gnostic philosophy.

Take the following from Robert Gundry:

“Plato’s dualistic contrast between the invisible worlds of ideas and the visible world of matter formed the substratum of Gnosticism, which started to take shape late in the first century and equated matter with evil, spirit with good.... Physical resurrection seemed abhorrent so long as matter was regarded as evil” (72).

Recall from Part One, where I identified the lie—that the body is evil because it is of the material world. But also recall that it is Adam’s flesh that Christ chooses to inhabit and, by extension, redeem.

While Plato’s doctrine says that the natural world is defective and that we ought to escape it, the gospel says that God loved this natural world so much that he sent his only begotten Son to rescue and then start the project of remaking it.

To quote Lewis yet again:

“Christianity is almost the only one of the great religions which thoroughly approves of the body—which believes that matter is good, that God himself once took on a human body, that some kind of body is going to be given to us even in Heaven and is going to be an essential part of our happiness, or beauty and our energy” (86).

With this idea in mind, I would argue that Plato’s influence on Christian thought regarding the immaterial aspect of the spirit has produced, if not an antichrist doctrine, something dangerously close to one.

Recall from 2 John that “many deceivers, who do not acknowledge Jesus Christ as coming in the flesh, have gone out into the world. Any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist” (1:7). If Christ chose flesh as the primary vehicle for rescuing creation,[1] what are we saying to him and about him if we reject flesh on the grounds of it being cumbersome to our “purer” and seemingly more spiritual disembodied souls?

Allow me to reframe the question in the affirmative. If Plato’s dualism seeks to lower and dissolve the same body Christ aims to raise and glorify, then Platonic dualism is opposed to Christ—i.e., anti-Christ.

(Note: some of you might be quick to reference Paul’s use of the word “flesh” in Romans and elsewhere to mean something opposed to a more spiritual mode of being, but that word in context refers to our pattern of sinful habits in Adam’s fallen condition and thus our failure to meet the requirements of God’s Law, which Jesus does meet. But luckily for me, I have not set out to expound on Romans, so I’ll leave it at that for now).

To be human is to be created in God’s image, and to carry out this daunting task requires a body in some shape or fashion. And while our bodies may be of the Adamic corruptible sort for now, the incorruptible and indestructible life of which Jesus is the glowing prototype will soon overtake it.[2]

Or, to remix Paul, we will not be finished blinking before the lightning has struck.[3]

Assumption 3: As spiritual beings, humans possess innate immortality that allows the spirit or soul to transcend bodily existence when the body dies.

This is an extension of the second assumption and, like that idea, stems from Gnostic teachings that were mainly foreign to first-century Judeo-Christian thought. According to Gundry, “the contents of a Gnostic library discovered in the 1940s at Nag Hammadi, Egypt, give evidence that a full-blown Gnostic mythology did not yet exist at the time Christianity arose” (73).

Yet, we know that while the Sadducees rejected the soul’s immortality and the resurrection from the dead, the Pharisees subscribed to and upheld both ideas. Thus, questions of immortality and resurrection were circulating when Christ entered the scene.

But when Christ enters that scene, he begins the work of resetting and reframing messianic and soteriological expectations (excluding Luke 20:39, where we see the Pharisees openly agreeing with Jesus while still failing to grasp the scope of his intentions).

Furthermore, two things become clear in Jesus’ dealings with these unique groups:

The Sadducees revered the Pentateuch as an ultimate good; Jesus said that he came to fulfill the same and that it all pointed to him.

The Pharisees revered the spirit of the Law and hoped for a resurrection of the dead; Jesus embodied the Holy Spirit through a life of compulsive obedience (Torrance, 19) and said he was the resurrection.

Suppose I diverge from the Pharisees’ notions regarding the soul’s immortality. In that case, I do so with the following logic: to say that we possess something innately transcendent, such as an immortal soul, is to say that we don’t need the Incarnation, which would be to shroud our Christology in vague, shadowy incoherencies.

Because of such incoherencies, we might often hear someone claim, in an off-handed way, that all religions are essentially the same. But the problem with Christianity is that, in its truest form, it is not a religion at all—it is a person.

Remember that Paul was also a Pharisee (and a good one) until he met the risen Jesus on the Damascus Road.[4] But Paul’s experience and knowledge as a Pharisee could only get him so far. In the end, his former theology gave way to a higher Christology. So, perhaps we can employ a pinch of caution before adopting a Pharisee’s perspective.

Biblically speaking, if we do possess immortality, it is only because immortality is innate to Jesus himself, for in him, “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:29).

If I may be allowed a cliché, emphasis is everything.

The Errors

Now that we have covered the assumptions, let’s move on to the errors. The topical question’s first fundamental error is that it is not biblical. And by that, I mean if you search for it in the Bible, good luck on your quest.

And while I have already explained how and why the question’s inference from scripture is suspect, some might still say, “Well, the Trinity is never mentioned in the Bible either, but we have defendable evidence that it was a concept in circulation among the early church.” Very well (regarding the Trinity).

But while the contemporary, Americanized church insists on the postmortem reward of going to Heaven and escaping eternal hellfire—and has the nerve to call this soteriology—I believe the New Testament insists on a solution more applicable to the problem at hand: “your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10).

Indeed, the Lord’s prayer is not for our disembodied souls or spirits to shuffle off their mortal coils and ascend skyward. Rather, the prayer is that God’s kingdom will come to earth because it is his will to dwell among us in bodily form and launch the grand campaign of setting right a world gone wrong.

The question’s second fundamental error is not as much a scriptural error (though it still is to a degree, which I intend to demonstrate) so much as a logical one. And the most logical answer I might give to the question, “Do you know where you would go if you died today?” would be, “No, and neither do you.”

To be clear, I can and should deliver this reply with all due respect. But if you still contend that you know for sure, I ask you to return to the same Bible on which you establish your belief and consider the following admonition: “continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling” (Phil. 2:12). In other words, avoid certainty like the plague.

Meanwhile, the most biblical answer might be to quote the Psalmist: “When their spirit departs, they return to the ground; on that very day their plans come to nothing.” (Psalm 146:4). The writer of Ecclesiastes echoes this idea when he writes, “in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom” (9:10).

Paul, speaking in the light of Christ’s resurrection, chose different language but conveyed a similar idea: “Brothers and sisters, we do not want you to be uninformed about those who sleep in death, so that you do not grieve like the rest of mankind, who have no hope” (1 Thess. 4:13). Paul then emphasizes Christ’s resurrection as the hope for those who have fallen asleep (which solves the infant mortality dilemma we wrestled with earlier).

This is crucial for reorienting our traditional view of afterlife toward a more biblical framework of understanding 1) death as the consequence of sin and 2) Jesus as the person (body) through whom death devours itself from the inside out.

Please note that I gave the logical response before the biblical to draw attention to the apparent fact—no one can know what happens after death because the only way to know, scientifically, is to die. That goes for the biblical authors, as well. And for now, I’m going to exclude NDEs (near-death experiences) to ascertain “proof,” given the volume of intense debate within that field of study, not to mention that people of different faiths often report experiences that only serve to reaffirm their religious persuasion.

Instead, my emphasis remains on the biblical thinking about death, which the authors rendered not in terms of afterlife but rather in terms of 1) Adam’s curse (a.k.a., the Fall) and 2) Christ’s redemption of the created universe.

In the OT, death is a cessation of being: “By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return” (Gen. 3:19). The point here is that death, according to Genesis, is a curse (an idea we will revisit).

In the NT, death is a place or state of slumber for those in Christ. For those outside of Christ, it is the same sleep, but one where the waking will be to an everlasting judgment (2 Thess. 1:9).

So, with the evidence I have given thus far, I am troubled by a conundrum: Christians believe that the dead in Christ are in Heaven with God, yet Christ himself could not ascend to his Father in Heaven until after he rose bodily from the dead.

Perhaps one could argue that his ascension provides a place for those who sleep. But, if they who sleep in Christ are with God in spirit (whatever that means), I find it odd that the rules applied to Christ as the Son of Man do not apply to the rest of us. To be clear, I am not saying it is impossible, but that I find it odd.

According to Romans, Paul believed that the key to sonship was the physical resurrection of his body from the dead, for it was the Resurrection that vindicated Christ as the firstborn Son of God (1:4):

“We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we were saved. But hope that is seen is no hope at all. Who hopes for what they already have? But if we hope for what we do not yet have, we wait for it patiently” (8:22-25).

If you are of a more charismatic persuasion, perhaps you will tell me that you have already been adopted into sonship. Congratulations, with all sincerity. Meanwhile, I still wait for my body to be redeemed. This is the hope for which my spirit groans, the elemental construct to which I must return to be remade.

Forgive me if I am not satisfied with my adoption being limited to a heart-warming but otherwise useless metaphor. I can call myself a son all day long. But until I am vindicated by the power of either transfiguration or resurrection (whichever comes first), I am a candidate for sonship only.

Faith produces the righteousness (sonship) over which death has no power. But to be vindicated by faith as a son of God, I must become a new creation just as Christ became and inaugurated the New Creation when he walked out of his tomb.

And this next point is even more critical: I have no victory, inherent immortality, or eternal nature apart from these characteristics summed up in and through the Incarnation and the Resurrection.

And neither do you.

Death Defeated

Earlier, I mentioned that I would revisit the point of God pronouncing death as a curse on Adam and his generations as the penalty for sin. Allow me to return to it now within the context of a more radical claim that, once again, hails back to my assertion in Part I about atheism being the better way forward.

Here goes nothing: the atheist view of what happens to a person when they die is more biblical than the so-called Christian view.

Now, what am I up to here?

The atheist believes that when a person dies, that’s it—no more thoughts, no more consciousness. Recall my earlier quotations from Psalm 146 and Ecclesiastes 9 affirming the same view. But here, some might quote Isaiah: “The realm of the dead below is all astir to meet you at your coming; it rouses the spirits of the departed to greet you— all those who were leaders in the world; it makes them rise from their thrones—all those who were kings over the nations” (14:9).

This could counter my claim, except for what we encounter in Jonah: “From deep in the realm of the dead I called for help, and you listened to my cry” (2:2). We know from that story that Jonah is not dead; he is trapped inside a giant fish.

If Jonah can get away with referring to the realm of the dead with poetic license, then so can Isaiah. We might even affirm that the biblical authors used poetic language to convey ideas for which they had no other rubric (Jesus was in the same habit, but more so for our benefit).

If the biblical language surrounding death is more often poetic than literal, what can we conclude about death as an inescapable reality? Well, the first thing we ought to conclude is that death is evil and adversarial to God’s intentions for humanity, and the second is that “sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned” (Rom. 5:12).

Consider the following dilemma: if the atheist is wrong, and we find after death an afterlife where the faithful ascend to Heaven and the unfaithful crowd into Hell, what exactly did Christ achieve?

What is the point of defeating death (1 Cor. 15:26) and bodily rising from the grave if, on the other side of death, we enter eternity as uncoupled, disembodied souls? That does not sound like a penalty (though Hell certainly does), and death does not sound like an enemy—at least not an enemy that warrants thwarting via the largest-scale rescue mission of all time.

Recall one of my earlier remarks, now edited for clarity: the Platonic doctrine of disembodiment harms our Christology because it downgrades death from an enemy to something more like a nuisance.

For death to be a significant consequence of sin, it must impress us with its finality, just as it impressed Christ’s disciples when his body was taken down from the cross and entombed. Did they host an after-funeral homegroup to assure one another that Jesus was safe at home (with himself?) and could finally rest in peace?

No, they did not have the luxury we take for granted of entrusting their belated friend and relative to a higher power. How could they? Their Lord was dead, and he was the higher power, or so they had vainly hoped. That’s the point—death is final. It always has been for the just and the unjust alike.

Or, at least, it was until Jesus upstaged it.

But because the disciples failed to understand the prophets concerning Jesus’ death and resurrection (Luke 24:25-26), they endured a weekend of quiet hopelessness as they came to grips with a brutal reality. At worst, their Lord was a false messiah. At best, he was a wise, righteous prophet who, like all God-fearing Jews before him, would rest safely in Abraham’s bosom, meaning he would be protected in God’s promise to Abraham and sealed in Abraham’s righteousness (Hebrews 11:39-40).

Luckily, we know better because we know the rest of the story. We know that “as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive” (1 Cor. 15:22). The dichotomy is self-evident, and nowhere in that dichotomy is space given to a disembodied afterlife. If I have made any point, I hope it is this—afterlife, by its nature, is antithetical to God’s will as manifested in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus himself.

Or, to quote N.T. Wright (I take every chance I can get):

“The traditional picture of people going to either heaven or hell as a one-stage, postmortem journey represents a serious distortion and diminution of the Christian hope. Bodily resurrection is not just one odd bit of that hope. It is the element that gives shape and meaning to the rest of the story of God's ultimate purposes” (par. 2).

As I said, the atheist view of what happens to a person when they die is fundamentally more biblical than the so-called Christian view. But the genuinely biblical view is even higher resolution, for it says, through Jesus: “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live, even though they die; and whoever lives by believing in me will never die” (John 11:25-26).

I make no claims to understand this affirmation’s mechanics other than to say and to drive home yet again my thesis: where we go seems far less biblical than who we know—and the “who” claims to be the resurrection and the life.

Models and Semantics

If you are still with me, I want to emphasize a point lurking in the subtext of my claims, which I have yet to bring to light. If there is a state of being in God’s presence after death but before a literal resurrection in Christ at a certain point in time, and if we want to characterize that state as a Heaven where we enjoy the rewards of eternal salvation, fine by me. Indeed, I welcome that reality.

But my point remains: such a reality can only exist because Christ “is before all things, and in him all things hold together” (Col. 1:17). In other words, it is only through an Incarnational lens that such a reality can be conceived, much less be said to exist.

Still, I maintain that the Bible and its authors are not the least concerned with afterlife. Instead, the Bible emphasizes eternal life through New Creation, where the timeline is not linear but circular. All who lived and died before Christ and all who live and die after him will be caught up in the same Exodus event that we call the Resurrection. This is the hope in which we are saved.

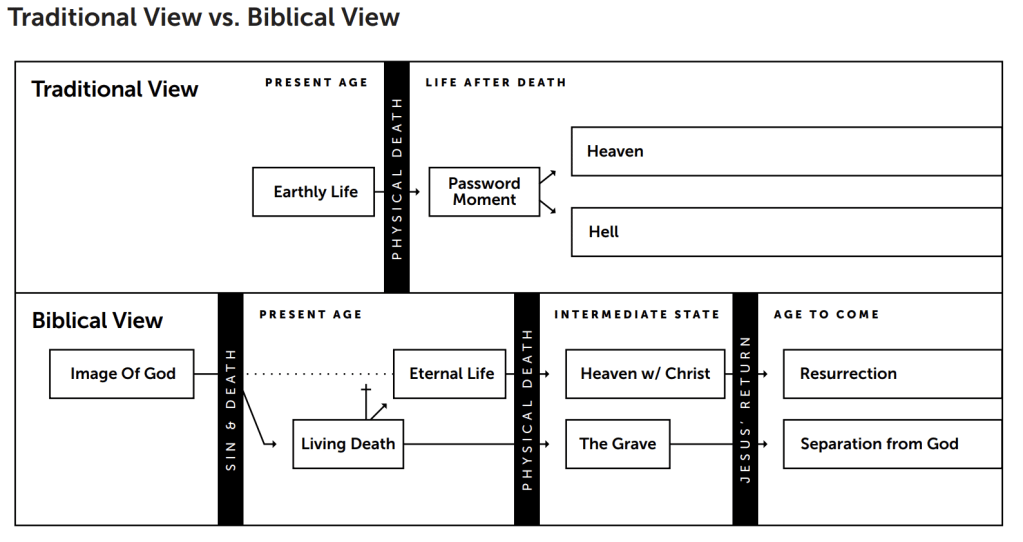

As to how we envision such a timeline, observe the following diagram called “Tragedy and Hope: Biblical Perspectives on Heaven and Hell.”[5]

In this graphic inspired by Tim Mackie's podcast, “Heaven w/ Christ” appears as an intermediate state that follows physical death. As I recall, N.T. Wright also uses a similar analogy in his phrase, “life after life after death.” Again, this is fine by me (and I defer to the Ph. D.s whenever I can).

But as I viewed the diagram and considered its linear implications, I was reminded of something I once read in a science textbook, where I had to study a model of atomic and subatomic particles.

The first thing I remember from that textbook is not the structure of the particles (which has long since passed through my mental incinerator to make room for less lucrative interests), but rather a disclaimer offered alongside the models, which read something like this: these are simplified representations.

While I think the above timeline is an ingenious way to capture the split between the traditional view of “afterlife” and the biblical view (which I hope I have emphasized), it is prone to the same limitations as the textbook. It is what N.T. Wright might refer to as a “broken signpost,” pointing us toward the final reality but not the reality itself.

The medium is not the only limitation. We struggle to envision a reality where God unravels time and space into their divine and final states, not to be abolished but to culminate in Christ as more time and space than we can yet comprehend. At the risk of sounding mystical, we might one day find a reality in which time and space are alive and, dare I say it, happily married—a mirror of the union between Christ and his spotless bride.

If I have lost you at this point, don’t worry; I have also lost myself. Suffice it to say that because of our conceptual limits, we have defaulted to the lowest-resolution image of the biblical hope in Christ by reducing that hope to a mere question of what happens to us when we die.

While such a question may be palatable to the lowest common denominator, I think I have a better one (or, if not better, at least more biblical): when the day of the Lord comes like a thief in the night, will we be ready?[6]

My question invokes an essential, underlying premise—if there is such a thing as a day of the Lord, then we might conclude that God intends to go on acting in time and space through both the person of Jesus and the infilling of the Holy Spirit, that is, Christ in us.

After all, time and space are the abode of bodies. Ironic that modern Christendom should emphasize man’s urgency to become a disembodied spirit when the Bible emphasizes the Holy Spirit’s urgency to become an embodied man.

Such urgency extends even to us, as Jesus lost no time in ascending to God’s right hand so that we might be filled with the same Spirit that raised him from the dead (Rom. 8:11). If my words seem too mysterious, only note whether they echo the teachings of scripture, then pause and reflect.

Outro

To put the original question to bed, allow me to answer it afresh within a biblical framework. If I died today, I have no idea where I would go—but I know to whom I belong. I have no desire to hypothesize what becomes of the mind or the soul after death, for my eyes are fastened on the hope and the mystery embodied in the one who defeated death.

Vague promises of eternal disembodiment in either Heaven or Hell have robbed us of the resurrection power that would set us apart from the systems of this world, both political and religious. We are not called to be people who escape the agonies of Hell to attain heavenly bliss. No, we are called to be people for whom death has lost its sting, even in the face of suffering and seeming defeat.

When we meet Christ and choose to walk with him, all questions of what happens after death slip away. Should we glance over our shoulder, we might see those questions stripped of their philosophical worth, laid bare by the desert winds. And then we might hear the Lord say to us, as he said to Peter, “What does that matter? You follow me.”

P.S. I know some of you are thinking: “But didn’t Jesus descend into Hell?” Good question. I hope to offer my thoughts on that in Part III.

Works Cited

Finochio, Gabriel. “Hell: Why Universalism is Wrong.” TheosU, 2022, https://my.theosu.ca/programs/hell?cid=1959621&permalink=hell-hot-topic-lesson-1

Gundry, Robert H. A Survey of the New Testament: 5th Edition. Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 2012.

Kraut, Richard. “Plato.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford University, Feb. 2022, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/plato/. Accessed 03 May 2022.

Harris, Sam. “The God Debate II: Harris vs. Craig.” YouTube, uploaded by University of Notre Dame, 12 Apr. 2011,

Lewis, C. S. “Mere Christianity.” The C. S. Lewis Signature Classics. New York, HarperCollins, 2017.

Mackie, Tim. “Tragedy and Hope: Biblical Perspectives on Heaven and Hell.” Exploring My Strange Bible. BibleProject.com, https://d1bsmz3sdihplr.cloudfront.net/media/Study%20Notes/emsb-notes-heavenhell.pdf, Accessed 03 May 2022.

The Bible. New International Version. Bible Gateway, 1993,

https://www.biblegateway.com/

, Accessed 24 Apr. 2022.

Torrance, T.F., and Robert T. Walker. Incarnation: The Person and Life of Christ. Downers Grove, InterVarsity Press, 2008.

Wright, N.T. “Heaven is Not Our Home.” Christianity Today, April 2008. https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2008/april/heaven-is-not-our-home.html, accessed 4 May 2022.

Footnotes

[1] See Romans 8:3.

[2] See Heb. 7:16 and 1 Cor. 15:53.

[3] See 1 Cor. 15:52.

[4] See Acts 9.

[5] Although the image and linked PDF are attributed to Tim Mackie’s podcast series, Exploring My Strange Bible, I cannot verify if his team developed this resource.

[6] See 1 Thess. 5:2, 2 Pet. 3:10, and Rev. 16:15.